OVERLOOKED: 30 Years After ADA Legislation, College Students with Disabilities Continue Fight for Inclusion

The comments about how my needs were too much for the system to handle still echo in my ear. I can hear the conversations that handcuffed my family. As we stepped into 804 University Ave — home of Syracuse University’s Center for Disability Resources — for the first time, we were escorted to the large conference room. My parents picked three consecutive chairs, pulled the middle one out. My mom sat on my left, dad on my right. We hoped to get a head start on what we expected to be the biggest transition of my life — and the most difficult one. It wasn’t only from high school to college, but from childhood to adulthood as well. It was a transition that we always wondered about, that revolved around independence — my independence and what, exactly, independence meant for me. The three of us had hoped the support in college would be more mainstream than in the public school system and that my needs would be more common. Turns out it’s the opposite. It was my needs, our problem. I was entering a system that continues to define people by what they can’t do instead of what they can do.

The Americans with Disabilities Act, which turned 30 over the summer, addresses accessibility, not inclusion, I quickly learned, and it’s the only thread guaranteeing my rights at this point. In high school, my rights were protected by the Individuals with Disabilities Act, but colleges have different responsibilities, based on the ADA, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Civil Rights Restoration Act. The responsibility of the disability shifts from being a shared task among the student, their family and the school to being of complete responsibility for the student. IDEA focuses on redefining independence, while the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act focuses on the traditional form of independence. Under Section 504, postsecondary institutions are required to provide academic adjustments to ensure equal educational opportunity — like extended testing time, priority registration, note-takers, sign language interpreters and accessible housing and make such accommodations — at no additional costs to students. They are not responsible for providing services based on personal needs, like eating.

The process was a two-year long dialogue and a continuation of Syracuse evolving into a more inclusive institution, says Michael Schwartz, associate professor at Syracuse’s College of Law. “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” he says. “Think of Syracuse University as an ocean-going liner; it takes time to adjust course. An external review of policies and practices of a billion-dollar institution with many schools, colleges, departments and units is a Herculean task.” It revolved around continuing the mission of disability advocates regarding eradicating the traditional approach to disability which centered on the cost of providing accommodations, says Schwartz, who co-chaired the committee with Joanna Masingila, dean of the School of Education. Schwartz says it was a lengthy process to choose from a limited number of qualified contractors equipped to undertake an extensive review of a complex institution like Syracuse.

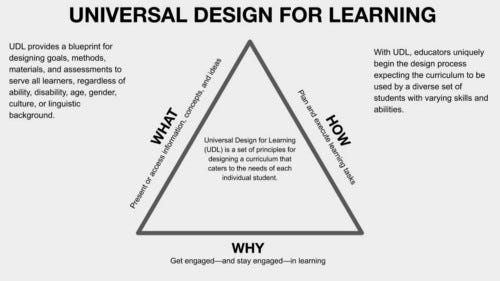

Paula Possenti-Perez, director of Syracuse’s Center for Disability Resources, adds that the review will help alleviate some of the Center’s biggest challenges. Though the Review will not directly address the issues regarding insufficient resources, space concerns and funding, it will help to create a culture and promote an universal design, which will reduce the need for accommodations, she says. Possenti-Perez says it piggybacks off the decision from over the summer to abandon the title “Office of Disability Services” in favor of “Center for Disability Resources,” representing the next step in the University’s transition from the medical model to the social model. As part of that, the plan focuses on addressing environmental barriers and enhancing community while individualizing support, she says. “The collective goal is to create inclusive and accessible environments and acknowledge disabled students, staff and faculty as valuable members of our community,” Possenti-Perez says. “My hope is that we, as a community, recognize our implicit biases and how pervasive ableism is in higher education.”

It’s a system that often forgets to include people with disabilities in diversity initiatives, says Stephen Kuusisto, director of Interdisciplinary Programs and Outreach at Syracuse’s Burton Blatt Institute. “The disability community is not always thought of as being part of what colleges like to call ‘diversity and inclusion.’ The irony is that the disabled are from every background and are the connectors between all diversity issues,” Kuusisto says, hoping that the External Review changes that at Syracuse. Though the committee plans to present more recommendations to Syverud after the new year, the most important one in Phase One could be the moving of the reporting line of the ADA Coordinator and Accommodation Specialist to the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, adds William Myhill, who has been Syracuse’s interim ADA/503/504 Coordinator since February 2018. “It positions disability properly within the family of diversity, and signals to the SU community that the work of these positions is equity work and not merely a matter of transactional compliance,” he says. Doing the bare minimum in terms of accessibility is not enough, Myhill says, because it may not offer true inclusivity.

But, Kuusisto adds, it comes from a larger, societal issue: it’s difficult to make progress because people without disabilities are often afraid to talk about disability. Kevin Camelo, who is a residential mentor for InclusiveU and has a sister with autism, adds that the taboo nature of contemporary approaches to disability creates a never-ending cycle of misinformation. “I think people are both under-informed and are scared to talk about disability. When they do recognize them, they do it in the way society has depicted disability,” he says.

Though these lines are flimsy, they remain stiff for those whom they impact on a daily basis and need services. Since Congress tried to address these issues in 2008, implementing the ADA Amendments Act of 2008. there’s been more of a recognition that accessibility is more than a wheelchair ramp, Myhill says. The law provided additional protection for people with invisible disabilities, who, historically, have been treated with “outright ableism,” Kuusisto adds. It increased the number of people protected under the ADA and required courts to approach disability discrimination cases trying to determine whether an entity had discriminated rather than determining if the individual seeking the ADA’s protection had an impairment that fit under a vague disability umbrella.

However, Jack and Nolan Willis ran into the same problems relating to inclusion as I did as they began attending Syracuse in August 2019. The brothers, both of which are wheelchair-users, have commuted from Fayetteville, NY, since they started at SU, originally hoping to someday live on campus. But they immediately found that doing so would be a major challenge. “While SU has offered to make physical accommodations when it comes to housing,” Jack Willis says, “finding help with respect to something like aids is a completely different hurdle and one I don’t think I’ll be able to overcome in the near future.” Like I was, the Willis brothers were told their needs were ones of personal matters. This has made it difficult to become part of the community as they once wished, Jack Willis says. It goes back to an experience in his Introduction to Engineering Computer Science course his freshman year. While the professor was accommodating, not having an assistant beside him made it difficult to navigate. The room was handicap accessible, but getting the door to the lecture hall open was challenging, Jack Willis says. He needed peers to help, a barrier that wouldn’t have existed if he had an assistant.

For myself and many others with disabilities, the lack of support has historically been ignored, Kuusisto says. Throughout history, people with disabilities, who are the strongest, most powerful advocates for disability rights, haven’t had the opportunity to speak for themselves. Reinforcing this oppressive model, universities have been behind in making disabilities more mainstream, Kuusisto says, Academically, the discrimination has had dier consequences, he says. According to a 2015 study from the National Council on Disability, only 34 percent of students with disabilities finish a four-year degree in eight years, dramatically falling short of the consistent national average of around 60 percent for all students. That needs to change, Kuusisto says. “Everyone deserves the accommodations they need to succeed. And the process of acquiring this support needs to be streamlined and made easier,”’ Kuusisto says. “Recreation, social opportunities, better transportation across the university, a recognition that disabled students are fully equal in every aspect of experience is what I hope for.”

Heading into the college application process, Helena Schmidt ran into frustrations relating to the lack of recognition of students with disabilities in higher education. Schmidt, a senior at Fayetteville-Manlius High School, is coming from the same inclusive environment as I did, where students with disabilities are given assistants to help with personal care. She told me she would need an one-on-one assistant to maximize her potential both academically and socially, and learning colleges don’t have to provide that support created additional stress. “I’m so used to always having help without question from the school, and I didn’t realize colleges don’t have to follow those guidelines,” says Schmidt, who is unsure where she will go next fall but will take classes at Cayuga Community College in the spring upon finishing high school. Schmidt says the lack of support in general society and within the current system prevents students with disabilities from obtaining the full college experience. “I can be more independent,” she says. “I don’t have to wait around for my parents to help me. They’re right there to help me do whatever I need or want. It’s especially important now that I’m getting older because I don’t want to be with my parents all the time.” Schmidt hopes to receive funding for a personal assistant through an advocacy group. For her, fighting with an institution and finding a solution would take years and undermine her academics in the process. She decided it wasn’t worth it. Her decision mirrors the conclusion I arrived at a couple falls ago.

In order to gain the independence I — and others with disabilities — want, the system suggests, it’s best to explore agencies, like Nascentia Health or Interim Healthcare, once we leave high school. The problem was that because of protections guaranteed through IDEA, I never needed an agency — my family has always taken care of me, — and in order to begin working with one, we would have needed to speedline a process that typically takes months. We tried to contact agencies, but found that what the higher education system largely considers medical, personal needs — things like eating and drinking — the insurance companies consider issues of convenience.

I traveled on thin, wobbly lines my entire life. I imagined these lines as hair-thin. But, when confronted, these lines transformed into bold, thick, heavy, and immovable barriers anchored in an outdated system, one that tells us we possess the freedom to speak but denies us the freedom to be heard and one that mires people with disabilities in an endless muck of ignorance, legalities, and indifference. Nobody cares until they have to care, until marginalized groups occupy buildings and streets for days, weeks, months. We remain stuck because we lack the numbers to demand change through mass protests, because we have no coalition that people without disabilities buy into. Those without disabilities often don’t care unless they have an emotional investment through a friend or family member, but even those who love us most — and devote their lives to us — don’t and can’t fully understand. It’s impossible, but some who hold elite degrees claim it is, claim that a piece of paper overpowers life experiences. The bottom line is: we need to be empowered, and colleges and multinational universities, in claiming to be progressive investors in the younger generation, reinforce the exclusionary ableism that’s become commonplace and invisible to most. But it’s as simple as this: Syracuse will have employees — Department of Public Safety officers — escort intoxicated students to their dorms, but tells me it’s too much to have someone there to help me eat while I’m on campus. It leaves us stuck — stuck because we’re supposed to fit a system, even though doing so means telling ourselves to accept schools, colleges, universities and the world wasn’t built for us.